In service of Karachi's dead

A father and son duo who work as post mortem specialists recall Karachi’s violent history which they have together literally dissected over the last 50 years.

Karachi: When Saleem digs in his blade into a gunshot victim, his hand doesn’t shiver. He says he blocks out all his thoughts so that he can focus on his mission to retrieve the bullet, which according to instructions handed out to him, he must at all costs.

As the on going violence in the city spirals out of control, there are people like Saleem, whose workload literally increase with the death toll of the day.

Working at the mortuary as an attendant for the last 16 years, his job is to preserve the evidence of injuries to the victims no matter what the nature of incident might be. It could be poisoning, accident, homicide or bomb blast case. But whenever a body turns up on his table, he must work like a robot.

Although illiterate, he will tell you the names of each bone and organ in a human body like any fresh medical graduate.

“Everything I learnt about this job, I learnt it from my father,” he says as he uses a bone cutter to cut through the ribs.

Between father and son, Inayat Masih and Saleem Masih, there is at least 50 years of post mortem experience. If you ask them how many post mortems they’ve carried out to date, they will look at each other with a bewildered expression, and say “hundreds…or maybe thousands.”

Because of their nature of work, which is considered one of the grimmest and lowest paying jobs in the world, both individuals have had a unique insight into the unrelenting violence in Karachi over the decades.

Inayat and Saleem belong to the minority Christian community. While the 70-year-old father has retired from the Civil Hospital Karachi after a 40-year service in 2001, his middle aged son Saleem continues to work like his dad as a Mortuary Attendant at the Jinnah hospital.

Although by law, a qualified doctor and designated Medical Legal Officer is supposed to carry out post mortem examinations, it is common knowledge that “none of the doctors like to get their hands dirty” when it comes to cutting up bodies and looking for forensic evidence that can be held up in the courts. It is left to these mortuary attendants to do the ‘dirty job,’ while all the MLO does is sign or alter the findings made by them.

Septuagenarian Inayat, who now lives a retired man’s life with his three sons, grandchildren and wife at a modest house in Akhtar colony, said he was only 18 when he had joined the profession in 1960. “At that time my salary was Rs56,” he says. By the time he retired, he was being paid around Rs 3,500. His son, after more than 15 years of service, earns a bit better than him and gets about Rs15,000.

These are meager sums for the low grade government employees whose common working hours last anywhere between 12 to 15 hours and at times even more depending on what kind of chaos is unfolding in the city.

Inayat said when he had joined the profession, he was taught everything about post mortems by his Hindu ustaad (teacher) named Bhaga. “Initially, I used to be scared but then I told myself that all heavenly books have said that when someone dies, they come back alive only on the day of judgment, not before that” he said.

Saleem said he too was afraid when he started out until his father chose a unique method to take away his fears. “I put both his hands on the body and made him feel the dead,” the father explained as he smiled. “Since then, my hand stays steady when I’m busy in my work,” Saleem said.

But does this mean that they’ve become numb after witnessing so much horror on their mortuary slabs? “No. We are human too. We too have a heart. It pains to know that one human being can do something as grotesque as cutting another human being in pieces,” Inayat said. It’s just that they don’t let their emotions take the better of them when they are at work.

When asked why did they choose this grim line of work, Inayat said he believed they were two benefits in doing this job. “Firstly, there is this sense of responsibility and achievement in providing justice to the dead, especially to someone who has been murdered. Secondly, you get money for what you do.”

According to the less philosophical Saleem, “it’s like any other job which one does to provide food and shelter to your family.”

When asked what was the worst time of violence he has witnessed in the city, Inayat said “I’ve seen a lot of bad times over the decades.” From the violence unleashed by Gen Ayub’s son in the 60s to the ethnic and sectarian violence that unfolded in the post Gen Zia era, he recalled all of them.

Inayat said that during the 60s and 70s, rarely were there cases of gunshot victims. “Mostly we dealt with accident cases and the occasional ‘chakoo’ (knifed) victims,” he said. However, it was during the Gen Zia’s time when gun shot cases became frequent. “This was also the time when heavily armed men began standing outside our mortuary to threaten us and doctors if we didn’t come up with findings according to their expectations.”

Saleem said now with the frequent waves of target killings, it has become a routine for them to get threatened and sometimes even beaten up by the victim’s sympathizers. “I ask what is our fault. We just do our duty,” he said.

Inayat said it was during Gen Naseerullah Babar’s operation in Karachi when trussed up bodies of victims started to turn up in gunny bags and eventually onto his mortuary table. Saleem says the trend continues to this day.

When asked what was the worst case they ever dealt with, the father and son were at a loss to explain which case could be considered worse than the other. Was it the ‘worms and insects laden’ foul smelling bodies which they first have to clean with their hands before dissecting it? Was it the child whose limbs were severed in the bomb blast? Or that body of a young man that had been pumped with a hundred bullets? Or perhaps the exhumation of a 50 day old body? They debated this among themselves without arriving on a conclusion. Each was worst in its own way.

But when asked who was the popular personality they operated upon, Saleem immediately said it was he who had conducted the post mortem on the notorious dacoit, Rehman Baloch, who was killed in an alleged shoot out with the police.

Inayat, however, had a regretful expression. “The ‘chocolaty hero’ Waheed Murad was supposed to land on my table at the civil hospital when he died [in 1983],” he said. Although Murad had died in Karachi, his body was taken to Lahore without a post mortem. “Bach gaya woh meray haath say (he slipped right through my hands),” he joked.

Police surgeon Hamid Parhyar said there was no doubt that attendants such as Inayat and Saleem were the backbones of a mortuary. “Simply put, without them a mortuary is incomplete.” There are at least eight such attendants at government hospitals in the city, four in Jinnah and four in Civil hospitals.

He said he would not contest the fact that most MLOs donot carry out the post mortems themselves. However, he said doctors and attendants face great dangers of violence at the mortuary, especially in target killing cases. “Some doctors have stopped going to the mortuary all together and leave everything to these attendants,” he said.

He agreed that the government should take measures to give better wages and equipment to mortuary attendants. “Apart from physical violence, they are exposed to the extreme health hazards of HIV and hepatitis since many of them work without proper protective gear such as thick gloves or mask,” Parhyar said.

This story was first published in the Express Tribune in two parts on April 29, 2012: https://tribune.com.pk/story/371596/mortuary-attendants-part-12-the-caretakers-of-the-dead/ and April 30, 2012: https://tribune.com.pk/story/371979/mortuary-attendants-part-22-recalling-a-history-of-violence/

|

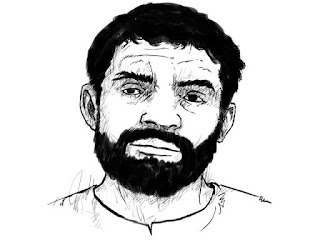

| Saleem |

As the on going violence in the city spirals out of control, there are people like Saleem, whose workload literally increase with the death toll of the day.

Working at the mortuary as an attendant for the last 16 years, his job is to preserve the evidence of injuries to the victims no matter what the nature of incident might be. It could be poisoning, accident, homicide or bomb blast case. But whenever a body turns up on his table, he must work like a robot.

Although illiterate, he will tell you the names of each bone and organ in a human body like any fresh medical graduate.

“Everything I learnt about this job, I learnt it from my father,” he says as he uses a bone cutter to cut through the ribs.

|

| Inayat |

Because of their nature of work, which is considered one of the grimmest and lowest paying jobs in the world, both individuals have had a unique insight into the unrelenting violence in Karachi over the decades.

Inayat and Saleem belong to the minority Christian community. While the 70-year-old father has retired from the Civil Hospital Karachi after a 40-year service in 2001, his middle aged son Saleem continues to work like his dad as a Mortuary Attendant at the Jinnah hospital.

Although by law, a qualified doctor and designated Medical Legal Officer is supposed to carry out post mortem examinations, it is common knowledge that “none of the doctors like to get their hands dirty” when it comes to cutting up bodies and looking for forensic evidence that can be held up in the courts. It is left to these mortuary attendants to do the ‘dirty job,’ while all the MLO does is sign or alter the findings made by them.

Septuagenarian Inayat, who now lives a retired man’s life with his three sons, grandchildren and wife at a modest house in Akhtar colony, said he was only 18 when he had joined the profession in 1960. “At that time my salary was Rs56,” he says. By the time he retired, he was being paid around Rs 3,500. His son, after more than 15 years of service, earns a bit better than him and gets about Rs15,000.

These are meager sums for the low grade government employees whose common working hours last anywhere between 12 to 15 hours and at times even more depending on what kind of chaos is unfolding in the city.

Inayat said when he had joined the profession, he was taught everything about post mortems by his Hindu ustaad (teacher) named Bhaga. “Initially, I used to be scared but then I told myself that all heavenly books have said that when someone dies, they come back alive only on the day of judgment, not before that” he said.

Saleem said he too was afraid when he started out until his father chose a unique method to take away his fears. “I put both his hands on the body and made him feel the dead,” the father explained as he smiled. “Since then, my hand stays steady when I’m busy in my work,” Saleem said.

But does this mean that they’ve become numb after witnessing so much horror on their mortuary slabs? “No. We are human too. We too have a heart. It pains to know that one human being can do something as grotesque as cutting another human being in pieces,” Inayat said. It’s just that they don’t let their emotions take the better of them when they are at work.

When asked why did they choose this grim line of work, Inayat said he believed they were two benefits in doing this job. “Firstly, there is this sense of responsibility and achievement in providing justice to the dead, especially to someone who has been murdered. Secondly, you get money for what you do.”

According to the less philosophical Saleem, “it’s like any other job which one does to provide food and shelter to your family.”

When asked what was the worst time of violence he has witnessed in the city, Inayat said “I’ve seen a lot of bad times over the decades.” From the violence unleashed by Gen Ayub’s son in the 60s to the ethnic and sectarian violence that unfolded in the post Gen Zia era, he recalled all of them.

Inayat said that during the 60s and 70s, rarely were there cases of gunshot victims. “Mostly we dealt with accident cases and the occasional ‘chakoo’ (knifed) victims,” he said. However, it was during the Gen Zia’s time when gun shot cases became frequent. “This was also the time when heavily armed men began standing outside our mortuary to threaten us and doctors if we didn’t come up with findings according to their expectations.”

Saleem said now with the frequent waves of target killings, it has become a routine for them to get threatened and sometimes even beaten up by the victim’s sympathizers. “I ask what is our fault. We just do our duty,” he said.

Inayat said it was during Gen Naseerullah Babar’s operation in Karachi when trussed up bodies of victims started to turn up in gunny bags and eventually onto his mortuary table. Saleem says the trend continues to this day.

When asked what was the worst case they ever dealt with, the father and son were at a loss to explain which case could be considered worse than the other. Was it the ‘worms and insects laden’ foul smelling bodies which they first have to clean with their hands before dissecting it? Was it the child whose limbs were severed in the bomb blast? Or that body of a young man that had been pumped with a hundred bullets? Or perhaps the exhumation of a 50 day old body? They debated this among themselves without arriving on a conclusion. Each was worst in its own way.

But when asked who was the popular personality they operated upon, Saleem immediately said it was he who had conducted the post mortem on the notorious dacoit, Rehman Baloch, who was killed in an alleged shoot out with the police.

Inayat, however, had a regretful expression. “The ‘chocolaty hero’ Waheed Murad was supposed to land on my table at the civil hospital when he died [in 1983],” he said. Although Murad had died in Karachi, his body was taken to Lahore without a post mortem. “Bach gaya woh meray haath say (he slipped right through my hands),” he joked.

Police surgeon Hamid Parhyar said there was no doubt that attendants such as Inayat and Saleem were the backbones of a mortuary. “Simply put, without them a mortuary is incomplete.” There are at least eight such attendants at government hospitals in the city, four in Jinnah and four in Civil hospitals.

He said he would not contest the fact that most MLOs donot carry out the post mortems themselves. However, he said doctors and attendants face great dangers of violence at the mortuary, especially in target killing cases. “Some doctors have stopped going to the mortuary all together and leave everything to these attendants,” he said.

He agreed that the government should take measures to give better wages and equipment to mortuary attendants. “Apart from physical violence, they are exposed to the extreme health hazards of HIV and hepatitis since many of them work without proper protective gear such as thick gloves or mask,” Parhyar said.

This story was first published in the Express Tribune in two parts on April 29, 2012: https://tribune.com.pk/story/371596/mortuary-attendants-part-12-the-caretakers-of-the-dead/ and April 30, 2012: https://tribune.com.pk/story/371979/mortuary-attendants-part-22-recalling-a-history-of-violence/